Stewart Hoffman is the author of The Band Teacher’s Percussion Guide from Oxford University Press

(Watch all the videos related to this post: Teaching Lifts and Levels; Teaching and Playing Paradiddles; and Practising Paradiddles)

No matter what a drummer’s goal is – whether it’s to play in an orchestra, or a jazz, rock or marching band – playing paradiddles well is fundamental to his or her musical development.

Watch Practising Paradiddles, then send the link to your students for an effective, guided paradiddle practise session in real time.

What is a Paradiddle?

The paradiddle is an essential rudiment that’s often introduced early on in a school percussion program, so you’ll want to watch carefully that your students are playing paradiddles right.

It consists of four, equally spaced notes, starting with two single strokes followed by a double stroke, or “diddle”. The first note of the four is usually, but not always, played with an accent.

So if we’re starting on the right hand, the accented first note is followed by a second note on the left hand, which is then followed by the final two notes played on the right hand. That final “diddle” sets up the following paradiddle to start on the opposite hand. Now starting on the left hand, the pattern is L-R-L-L, and so on.

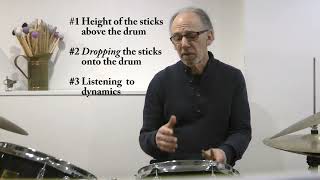

In this introduction to playing paradiddles, we’re going to focus on two important elements:

- the accented note played at the beginning of each paradiddle

- and the double strokes – the final 2 note “diddle”

The one thing we always keep in mind – the underlying concept that informs whatever we play – is that we play as efficiently and tension-free as possible.

To control accents and dynamics in general, and to help students play with a relaxed stroke, I teach a system called Lifts and Levels (watch the video here), which I incorporate into the teaching of paradiddles.

Playing the accent

The first thing to consider when playing paradiddles is how to play that accented first note.

Keep in mind that to play louder on a drum, we simply drop the stick from a higher level – as opposed to pushing or beating down harder onto the instrument. So we’re going to drop that accented first note from a higher level than the subsequent three, unaccented notes.

What drummers have to consider is that when a stick falls or is dropped onto a drum, it creates kind of a minor explosion, and if it’s dropped from a higher level, that explosion is going to have more energy. And you don’t have to “hammer” it down to get a solid rebound; just by dropping it, or gently tossing it onto the head when playing quicker passages, the stick bounces back. The challenge for percussionists is to learn to control, direct – and sometimes tame – that burst of energy off the drum.

Stiffening up and hammering that first, accented note into the drum, results in a loss of control. The stick bounces back, but a tense hand and arm won’t respond smoothly to that sudden burst of energy kicking back off the head, and won’t be able to efficiently manage the direction the stick takes. The drummer must lift the stick smoothly off the drum, in synch with that rebound.

The ability to control that rebound is fundamental to a good technique.

Playing paradiddles with “lifts and levels”

(View the video Teaching and Playing Paradiddles with Lifts and Levels here)

To start playing paradiddles, we’re going to incorporate 2 levels at roughly 12” and 2” above the snare drum: a 12″ level for the accented note and a 2″ level for the unaccented notes. (You can incorporate more levels, but for now, we’ll keep it to two.)

Starting with a right hand paradiddle, we set the right hand at 12” and the left hand at 2”.

For the first note, we drop the right hand from 12” and end the stroke at 2”.

For the second note, we drop the left hand from 2” and end at 12”.

And for the third and fourth notes, we drop the right hand from 2″ and end at 2”.

And now, we’re set up to play the paradiddle starting from the left hand.

At first, you or your students should play each stroke slowly and very deliberately, focusing on:

- Dropping, not pushing or hammering the stick into the drum. Think simply about releasing the weight of the drumstick, hand and forearm. We’re focusing on staying relaxed and thinking about weight and gravity to guide the stroke.)

- Again, review the video on lifts and levels. Don’t let the fingers flare out. Keep the 3rd and 4th fingers relaxed and curved under the stick to keep it under control when it strikes the drum. Don’t grab the stick when it hits the drum. With a tension-free hand stopping at the 2” position, and the curved and relaxed fingers remaining in position, the stick will pop back and stay in place.

Playing the “diddles”

After lots of (hopefully) slow, thoughtful practice, students will become more comfortable with the levels, and a tension-free, dropped stroke. The speed will come over time. But as the paradiddles get faster, we have to focus on keeping the diddles even by not allowing an uncontrolled bounce on that 2nd note of the diddle.

Students shouldn’t play a diddle – or double-stroke, for that matter, when playing an open roll (watch Teaching Double Strokes here) – by pushing the stick into the drum with a stiff arm and expecting to get 2 even notes. With that approach, you get a loud note, followed by a quieter note that isn’t necessarily rhythmically accurate. After an initial, relaxed drop onto the drum, that second stroke should be supported and controlled by a second, but smaller, wrist stroke. Smaller because that first stroke is going to rebound with so much energy that all you have to do is harness it and, with a gentle turn of the wrist, redirect the stick back toward the drum.

When playing paradiddles, it’s important to drop the notes from different levels – lower accents and higher unaccented notes – while still keeping clearly differentiated levels. Using smaller motions is a great way to develop control.

Keep in mind too, that students must always listen carefully to the sounds they’re creating. And teachers, make sure your students know what to LISTEN for:

- an even, 4-note pattern, with the accent and diddles sounding EXACTLY the same no matter WHICH hand the paradiddle begins on.

I encourage you to check out my Practising Paradiddles video, send the link to your students, and have them join me for a practise session in real time. The video will keep them engaged and focused as I guide them and provide a clear model for practising paradiddles.